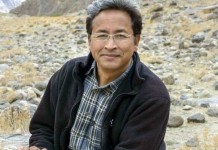

ALESUND, NORWAY: For a man who saved the world, or at least helped ensure that Adolf Hitler never got hold of a nuclear bomb, 96-year-old Joachim Ronneberg has a surprisingly unheroic view of the forces that shape history.

“There were so many things that were just luck and chance,” he said of his 1943 sabotage mission that blew up a Norwegian plant vital to Nazi Germany’s nuclear program. “There was no plan. We were just hoping for the best,” Ronneberg, Norway’s most decorated war hero, added.

The leader and only living member of a World War II commando team that destroyed the Nazis’ only source of heavy water, a rare fluid needed to produce nuclear weapons, Ronneberg has had his exploits celebrated in a 1965 blockbuster movie, “The Heroes of Telemark,” starring Kirk Douglas, been showered with military medals and been honored, belatedly, with a statue and museum display in his hometown here on Norway’s west coast.

M.R.D. Foot, the official historian of Britain’s wartime sabotage and intelligence service, the Special Operations Executive, which organized Ronneberg’s mission, described the raid on a Norsk Hydro plant producing heavy water in Nazi-occupied Norway as a “coup” that “changed the course of the war” and deserved the “gratitude of humanity.”

Yet Ronneberg, speaking softly over coffee and biscuits in the modest, white clapboard house overlooking a fjord where he has lived since 1947, explained that the whole mission – and perhaps the outcome of World War II – would have been very different had he not decided on a whim to go to the movies and then a series of pubs in England before parachuting into Norway in February 1943.

Still mentally sharp at his advanced age and still possessed of the unflappable calm that so impressed British military commanders more than 70 years ago, he recalled how, during a day off from training in Cambridge, England, in early 1943, he went to a movie theater and then happened “entirely by chance” to walk by a hardware store selling heavy-duty metal cutters. He decided to buy a pair on the off chance they might come in handy, and he took them on his sabotage mission.

Without this happenstance purchase, Ronneberg said, he and his men would never have been able to gain entry to and destroy the heavily guarded heavy water production plant at Vemork, in southern Norway. The handsaw that British planners had intended for use on a heavy padlock on the plant’s side gate, he said, would have taken too much time, made too much noise and alerted Nazi guards. The success of the mission “was mostly luck, definitely,” he said, smiling at his memories of a nighttime raid that, until the very end, had seemed a suicide mission.

Once inside a hall containing the heavy water production, Ronneberg planted two strings of explosive charges provided by Britain’s Special Operations Executive. He said he decided at the last minute to cut fuses designed to burn for 2 minutes so that they lasted only 30 seconds. This, he said, gave his men just enough time to get out safely, but made sure they would still be close enough “to hear the bang” and know “we had done our job.”

It took years before Ronneberg came to understand the exact purpose and importance of the job. All the British told him before dropping him onto a snow-covered Norwegian mountain, he said, was that a row of pipes at the Vemork plant needed to be destroyed.

“They just said it was important and had to be blown up,” he said, recalling his wartime exploits in his tidy living room, filled with family photos, including a large framed portrait of his wife, who died last year. The only hint of his past are a few books and magazines in an adjacent study devoted to the history of the war.

He added that he knew nothing at the time about nuclear physics, heavy water or the race to build a nuclear bomb. He knew that Britain had lost more than 35 men in a disastrous 1942 attempt to sabotage the Norsk Hydro plant, but he had no idea why it was so intent on disabling a remote mountain facility whose only product as far as he knew was fertilizer.

“The first time I heard about atom bombs and heavy water was after the Americans dropped the bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki” in 1945, he said. “Then we started to understand our raid and why.” And also that, had it failed, London could have ended up “looking like Hiroshima.” This belated realization of the huge stakes at play “was a tremendous satisfaction,” he said.

Historians have long argued over how close Hitler came to developing nuclear weapons. A German historian claimed in a controversial 2005 book that the Nazis conducted several nuclear weapons tests in 1944-45. But a more widely accepted view is that Hitler’s nuclear program, begun well before the Manhattan Project, stumbled badly because of its own inferior science and its enemy’s exceptional saboteurs.

It was handicapped by the flight and murder of Jewish scientists but suffered most gravely from a decision by the physicist Werner Heisenberg to use heavy water, deuterium oxide, instead of graphite, as a moderator in the production of bomb-grade uranium. Heavy water was not only less effective than graphite but also far more difficult to obtain in sufficiently large quantities, leaving the Nazis dependent on steady supplies from the Norsk Hydro plant in Norway.

All the same, Ronneberg’s raid slowed the Nazi’s pursuit of a bomb rather than delivering a knockout blow. The Nazis worked quickly to rebuild the plant at Vemork, prompting a series of bombing raids by the U.S. Army Air Forces that infuriated even anti-Nazi Norwegians because of the civilian casualties they caused. The Germans then tried to move all their surviving heavy water in Norway to Germany, but this effort collapsed when Norwegian saboteurs, led by one of Ronneberg’s team, Knut Haukelid, blew up a ferry carrying the prized cargo.

While long celebrated by foreign, particularly British, filmmakers, the exploits of Ronneberg and nine other Norwegians involved in thwarting the Nazi nuclear project became widely known in Norway only this year, when NRK, the state broadcaster, ran “The Heavy Water War,” a six-episode miniseries that became a national sensation. The statue of Ronneberg in front of City Hall here in Alesund was put up only last year to observe his 95th birthday.

Inscribed on its base is a message – “Peace and Freedom are not to be taken for granted” – that Ronneberg says has been ignored for too long by many in Norway, where painful memories of collaboration with the Nazis by the country’s wartime leader Vidkun Quisling and his fascist regime have stilled enthusiasm for too much digging into the past.

He said it was “quite incredible” that executives at Norsk Hydro, many of whom worked closely with the Nazis, were never prosecuted for their wartime treachery. The issue is still so delicate for a company that survived the war to become a pillar of the Norwegian economy that the television series broadcast this year altered the names of Norsk Hydro directors who had collaborated with Hitler.

A journalist and administrator with the national broadcaster for most of his postwar career, Ronneberg for decades avoided talking publicly about the 1943 mission but, worried that younger Norwegians knew little about the war, started to open up in the 1970s and has since spoken regularly at schools.

“There is a lot of talk about ‘never again,’ but this is impossible if we don’t remember what happened back then,” said Ronneberg, whose three children have all pursued careers outside the military. Remembering, he added, will only grow more difficult as his own generation dies off. “The challenge ahead is that it will be hard to interest people in history when there is nobody left alive who was a witness.”

Ronneberg still follows current events and, despite trouble walking, still occasionally meets with fellow veterans and also members of Norway’s royal family, whose forebears fled to Britain to escape the Nazis and helped rally resistance. This year he traveled to London to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the Special Forces Club.

He said he worries today about a newly assertive Russia and what he sees as the reluctance of many in Europe to understand that “it is not a stable world” and that peace is not guaranteed. “It ought to be obvious to people that peace and freedom have to be fought for,” he said. “Politicians seem to have forgotten this.”

This article was first published on The New York Times